Farida Akhter || Wednesday 05 November 2014

The World Health Organization (WHO) took the lead in 2003 to formulate a global treaty called the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) is an evidence-based treaty that reaffirms the right of all people to the highest standard of health. It was the first treaty that was designed in developing a regulatory strategy to address addictive substance, such as tobacco and that asserted the importance demand reduction strategies as well as supply issues. The FCTC was unanimously adopted on 21 May 2003, at the 56th World Health Assembly, and was opened for signature, for a period of one year, from 16 June 2003 to 22 June 2003 at WHO headquarters in Geneva and thereafter at United Nations Headquarters in New York, from 30 June 2003 to 29 June 2004. The Treaty has 168 Signatory member states of the WHO.

Bangladesh has signed the treaty on 16 June, 2003, ratified on 14 June, 2004 and formulated the national tobacco control law on 27 February, 2005. Bangladesh was one of the first very few countries to sign, ratify and to enter into force. In that respect Bangladesh is quite advanced in tobacco control policies undertaken at the national level.

The WHO FCTC has been in place for about a decade and has sparked great progress in tobacco control both domestically and internationally. However, implementation still presents considerable challenges in many countries of the world, specially the developing countries where tobacco industry has significant influence over the government and the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance in particular in countries like Bangladesh.

The member states of WHO created World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) in 1987 to observe the day around the world every year on May 31. It intends to encourage a 24-hour period of abstinence from all forms of tobacco consumption around the globe and to draw global attention to the widespread prevalence of tobacco use and to negative health effects, which currently lead to 5.4 million deaths worldwide annually. That is, the global action against tobacco has been there much before FCTC and at present WNTD plays a significant role in making FCTC known to the general public on this occasion and also helps in the implementation of the Tobacco control law.

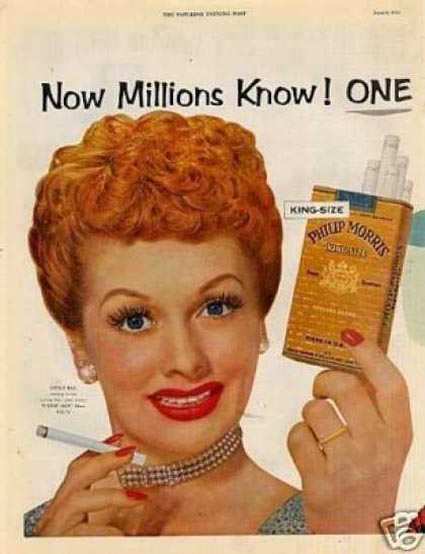

Till these days, tobacco control movement at national and international level has mostly focused on men, as smokers. “No smoking campaign” was targeted towards men mostly although big tobacco cigarette manufacturers always wanted women to be the consumers of their products. They produced attractive cigarette packets with pictures of attractive film stars of the western countries. Cigarette was a sign of smartness for both men and women. Yet tobacco control movement never attracted women’s groups and did not have any women-focused activism under the leadership of women.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) selected “Gender and tobacco with an emphasis on marketing to women” as the theme for the World No Tobacco Day (May 31, 2010). The attention was drawn particularly to the harmful effects of tobacco marketing towards women and girls. According to the estimates of WHO (2010), women comprised about 20% of the world’s more than 1 billion smokers. It was a concern that the epidemic of tobacco use among women was increasing in some countries. Women are a major target of opportunity for the tobacco industry, which needs to recruit new users to replace the nearly half of current users who will die prematurely from tobacco-related diseases. More than 1.5 million women die each year from the consequences of tobacco use. Without a clearly articulated gender focus in tobacco control policies, the yearly death toll among women will jump to 2.5 million by 2030. Of these avoidable deaths, 75 percent will occur in developing countries [ Gender Women, and The Tobacco Epidemic, WHO 2010 http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/gender/women_tob_epidemic/en/index.html ] According to the WHO Global Tobacco Control Report (GTCR), while rates of smoking among boys are leveling off in many countries, rates of smoking among girls are increasing.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) selected “Gender and tobacco with an emphasis on marketing to women” as the theme for the World No Tobacco Day (May 31, 2010). The attention was drawn particularly to the harmful effects of tobacco marketing towards women and girls. According to the estimates of WHO (2010), women comprised about 20% of the world’s more than 1 billion smokers. It was a concern that the epidemic of tobacco use among women was increasing in some countries. Women are a major target of opportunity for the tobacco industry, which needs to recruit new users to replace the nearly half of current users who will die prematurely from tobacco-related diseases. More than 1.5 million women die each year from the consequences of tobacco use. Without a clearly articulated gender focus in tobacco control policies, the yearly death toll among women will jump to 2.5 million by 2030. Of these avoidable deaths, 75 percent will occur in developing countries [ Gender Women, and The Tobacco Epidemic, WHO 2010 http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/gender/women_tob_epidemic/en/index.html ] According to the WHO Global Tobacco Control Report (GTCR), while rates of smoking among boys are leveling off in many countries, rates of smoking among girls are increasing.

The FCTC Article 4 is about the guiding principles to achieve the objectives of the Convention and its protocols; the Article 4.2(d) refers to the need to take measures to address gender-specific risks when developing tobacco control strategies. The Article 4.2(d) is as follows:

FCTC Article 4.2 (d): Strong political commitment is necessary to develop and support, at the national, regional and international levels, comprehensive multisectoral measures and coordinated responses, taking into consideration … the need to take measures to address gender-specific risks when developing tobacco control strategies.

In the Conference of the Parties (COP) the governing body of the WHO FCTC comprising of all Parties to the Convention, the Article 4.2(d) has not been a focus at any meetings. Conference of the Parties keeps under regular review the implementation of the Convention and takes the decisions necessary to promote its effective implementation. FCTC provisions have the potential to protect women and men alike, but this potential will only be realized when gender-specific considerations are included in the development and implementation of tobacco control policies. Lack of gender-focus meant a partial review of the implementation of the FCTC.

In the WHO reports this gap is now being recognized. For example WHO in its 2007 report Gender and tobacco control: a policy brief, “Generic tobacco control measures may not be equally or similarly effective in respect to the two sexes…[A] gendered perspective must be included…It is therefore important that tobacco control policies recognize and take into account gender norms, differences and responses to tobacco in order to…reduce tobacco use and improve the health of men and women worldwide”.

The major concerns for women are:

- Tobacco companies are targeting women for marketing of their products.

- The epidemic of tobacco use is increasing among women, particularly among young girls

- The rates of smoking is leveling off for boys, but rates of smoking for girls is increasing

- More women will die prematurely each year from tobacco related diseases

- The tobacco industry uses packaging and product design as part of its marketing to increase the attractiveness of tobacco use among girls and women

- Traditionally, smoking cessation programmes for women have tended to focus only on tobacco use during pregnancy and not for all other women

- Women are victims of passive smoking and suffer from various health problems without being smokers

- The use of smokeless tobacco products among women is high and also socially accepted , which poses great health threat

- The gender-specific mortality and morbidity data on smokeless tobacco use is not available

- Women’s involvement in tobacco cultivation poses health and nutrition threat, but it is not reported and recognized

- Women are involved in the production process of cheap smoking products such as bidi and in the production of smokeless products such as Zarda-gul.

- The tobacco-control measures are not gender-specific

Gender-specific tobacco control measures

The FCTC Article 4.2(d) has not been fulfilled till COP6 that was held in Moscow during 13 – 18 October, 2014. In the COP6, one of the Policy Briefing of Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) was called “Women cannot be Left Behind” and recommended to develop an expert report on gender and tobacco control. The report should include measures to address gender-specific issues when developing tobacco control policies and strategies as well as the development and utilization of women’s leadership in tobacco control. The report would be considered at COP7 with the aim of strengthening gender specific implementation of the FCTC at global and country level.

While the tobacco control strategies failed to address gender issues, the tobacco industry was not keeping quiet. The industry has developed sophisticated gender-based strategies to entice more girls and women into a lifelong tobacco addiction. Therefore, there is urgency for policy makers to incorporate gender indicators and gender-specific reporting requirements in their policies and programmes to counteract the industry’s efforts and save women from tobacco related diseases.

At the Conference of Parties, the world leaders call for accelerated implementation of the FCTC. However, there is still a big gap in taking specific measures to deal with the specific needs and life circumstances of women and girls in different countries according to the different social, economic and cultural differences. There is a lack of policy guidance to effectively integrate gender-sensitive measures in national tobacco control policies and programmes.

At the COP6, it was recommended that an expert report on measures to address gender-specific issues to be presented at COP7. The expert report may also provide specific suggestions on how to build up and capitalize on women’s leadership in tobacco control. Women cannot be left behind when it comes to addressing the number one cause of preventable death – tobacco use.

So far, the proposed gender-specific strategies include

- Gender specificity in Article 14: need to develop broader cessation programmes for girls and women should be both for pregnant and for all women. Cessation services and materials should be tailored to address women’s particular reasons for tobacco use and concerns about stopping, such as weight gain and dealing with stress.

- gender-specificity in Article 11 of the WHO FCTC: Tobacco control measures with regards to packaging and labeling should be carefully designed in order to have a strong impact on women and to ensure that they are adequately warned of the dangers of tobacco use. In this regard, dedicated pre-market testing of health warnings to assess their effectiveness on women, as well as men, is essential.

However, in the FCTC there are many other Articles that need to have gender-specific strategies. These are

- Gender-specificity in Article 6.2(a): implementing tax policies and, where appropriate, price policies, on tobacco products so as to contribute to the health objectives aimed at reducing tobacco consumption among women and girls.

- Gender specificity in Article 8.2: Tobacco control policies must emphasize on adoption and implementation of effective legislative, executive, administrative and/or other measures, providing for protection from exposure to tobacco smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places for protecting women and girls against passive smoking.

- Gender specificity in Article 12 (b): public awareness about the health risks of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke, and about the benefits of the cessation of tobacco use and tobacco-free lifestyles that affects women and girls

- Gender specificity in Article 14(c) establishes in health care facilities and rehabilitation centres programmes for diagnosing, counseling, preventing and treating tobacco dependence.

- Gender-specificity in Article 17: For the provision of support for economically viable alternative activities for female tobacco workers, women in tobacco growers’ families and, as the case may be, individual female sellers.

- Gender specificity in Article 18: For protection of the environment and the health of persons, particularly women and girls, in relation to the environment in respect of tobacco cultivation and manufacture within their respective territories.

Women’s Leadership in tobacco control

Although women are very much affected by tobacco use and its production, the women’s organizations have hardly picked up tobacco control as an issue for their activism. Even those who are working on violence against women do not relate tobacco use as a cause. However, at the international level there is recognition to the need of the complex issues of tobacco use among women and girls particularly on health grounds. The International Network of Women Against Tobacco (INWAT) was founded in 1990 by women tobacco control leaders much before the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) by WHO (www.inwat.org). From its website it is known that INWAT provides contacts, primarily women, but increasingly to men, to individuals and organizations working in tobacco control; collects and distributes information regarding women and tobacco issues globally; shares strategies to counter tobacco advertising and promotion; supports the development of women-centered tobacco use prevention and cessation programs; and collaborates on the development of publications regarding women and tobacco issues. INWAT believes that if tobacco use and exposure can be prevented or stopped, women’s health can be vastly improved. An international network of women against tobacco is considered as greatest strengths in achieving improved health and greater equality. INWAT Europe was established in 1997-1999 with funding from Europe against Cancer.

At national level, there is not much information on women’s alliances or network on Tobacco control activities in different countries. Only in Bulgaria, there is an Association Women Against Tobacco-Bulgaria. But not much information is available about their work. In Bangladesh, after the alert by WHO in 2010 about targeting of women by the tobacco companies for marketing of tobacco products to women, an alliance was formed against tobacco by the initiative of Narigrantha Prabartana and UBINIG. UBINIG as a research organization was conducting an intensive research on tobacco cultivation and its impact on food production since 2006 and Narigrantha Prabartana had a good networking with women-led organizations all o0ver the country. So in 2010, on the occasion of observing the World No tobacco Day (May 31) an alliance of women’s organization in about 54 districts of Bangladesh to engage in tobacco control activities and to protect women from the harmful effects of tobacco. The Bengali name for the alliance is Tamak Birodhi Nari Jote (TABINAJ). Its activities are being supported by Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK), USA. It is working on various aspects of tobacco consumption, tobacco cultivation, production and use of smokeless tobacco products. It has been active in the law amendment to include smokeless tobacco products in the definition of tobacco in the national law formulated in 2005. Now we are very active in law implementation issues, creating awareness and organizing women’s groups as champions of Tobacco control. The secretariat of TABINAJ is in the Women’s Resource centre called Narigrantha Prabartana narigrantha@gmail.com.

In Bangladesh, information about tobacco use by women is known through some surveys. According to Global Adult Tobacco Survey (2009),

- in Bangladesh 43.3% of adults (41.3 million) currently use tobacco in smoking and/or smokeless form.

- 44.7% of men, 1.5% of women, and 23.0% overall (21.9 million adults) currently smoke tobacco.

- 26.4% of men, 27.9% of women, and 27.2% overall (25.9 million adults) currently use smokeless tobacco.

- 63.0% of workers (11.5 million adults) are exposed to tobacco smoke at the workplace. Among them 30.4% are women at workplace and 20.8% in public places.

According the updates by Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (April, 2014)

- In Bangladesh, more than 95,000 people die each year from tobacco-related diseases.

- Each year, about 1.2 million cases of illnesses are attributed to tobacco.

There is however no gender disaggregated data on tobacco related deaths and illnesses. On the use of smokeless tobacco, some research data is available on women in reproductive age. The prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among reproductive-aged women was 20.1% in Bangladesh. Bangladesh recently passed amendments to its national tobacco control law, Smoking and Using of Tobacco Products (Control) Act, 2005. Smokeless tobacco products were brought under the ambit of the law, which means that advertising of smokeless tobacco products will be prohibited and smokeless tobacco packaging must display large, graphic health warnings. The importance of the inclusion of smokeless tobacco products under the law in Bangladesh cannot be overstated. With coverage of smokeless tobacco products, roughly 21 million women who were previously overlooked by the law will now be warned about the deadly effects of the tobacco products they use. [Source:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Tobacco Use and Secondhand Smoke Exposure Among Women of Reproductive Age – 14 Countries, 2008-2010. MMWR 2012;61:877-882] .

Tabinaj carries out action programmes as well as collects information to strengthen the network and be effective in their campaign. A country-wide investigation by the Anti-Tobacco Women’s Alliance (Tabinaj) identified 130 brands of jarda (chewing tobacco) and 12 brands of gul (powdered tobacco) produced in 35 districts. Jarda and gul are the major smokeless tobacco products. Other such products e.g. sadapata and koinee are not much prevalent and are not commercially marketed. Women are consuming these products without any social resistance, because these are common practice at home and public places. The inclusion of smokeless tobacco in the definition of tobacco in the amended law has been one of the primary works of Tabinaj advocacy.

Tabinaj also works on the issues of effects on women by tobacco cultivation and women as workers in bidi factories. Tabinaj is active in all those areas and continuously raising the concerns through meetings, human chains and campaigns.

Tobacco consumption and production is harmful for both men and women. It is time that women come forward and take leadership in tobacco control not only to protect women but also men and children.

Let women of the world unite against tobacco.

Also visit Framework Convention Allaiance